When is the last time you engaged with the negative impacts or harms perpetuated by nuclear reactors or the nuclear fuel cycle? For many nuclear engineers and nuclear energy advocates, we primarly engage with these subjects during, or to prepare for, debates and heated discussions with detractors and skeptics. In these moments, the primary argument is that we believe nuclear energy is a net positive, and in fact carries many qualities that are attractive to environmentalists. In fact, I’ve made these very points myself, including in a 2019 Earth Day blog post for the Nuclear Energy Institute.

This Earth Day, I’m going to ask for something different.

In the course of my research, I’ve gotten to study the movement of nuclear materials throughout the nuclear fuel cycle, from cradle to grave if you will. While I’m far from unique in my expertise, I’ve found that most nuclear engineers, and the more general category of nuclear energy advocates, are much less familiar with the risks, accidents, and harms that have occured outside of nuclear reactors, in the rest of the fuel cycle.

I was asked to speak at the American Nuclear Society’s nebulously-titled Earth Day webinar, What Does Earth Day Mean To You? with some real powerhouses of the nuclear energy think tank and influencer world*. I figured that I could play to my strengths, and also take advantage of this small megaphone to talk about topics that I doubted anyone else on stage would spend their precious few minutes discussing.

I think that every nuclear engineer and nuclear advocate should be aware of accidents and issues that have happened in the nuclear fuel cycle, just as we learn about accidents at nuclear reactors. The more we understand about the complicated legacy of the uranium lifecyle, the better we are at building towards a better future. The more we know about the past, the more effective we can be at avoiding the same pitfalls at tragedies. The more we are faced with the continuing legacy of contamination, the more likely we are to push for more funding to remediate the land and compensate the victims.

If you missed the actual webinar, ANS will upload it and make it available to everyone, including non-members, on their Webinar Archive.

For those of you directed here by the webinar itself, welcome! I promised you resources, and although they aren’t extensive, the following list will provide you with a good foundation to dive into the topics I mentioned.

I intended to curate a longer list, but I received an unexpected call the day before the webinar (4/21) informing me that a local(ish) clinic had a vaccine appointment cancellation, and would I be able to drive 75 minutes away to get there before close of business? I’m now a proud owner of a sore arm and my second dose of COVID-19 vaccine, but I lost several hours of my day and now feel varying levels of sick, depending on the moment.

Abandoned Uranium Mines (AUM)

Book: The Navajo People and Uranium Mining

Edited by Doug Brugge, Timothy Benally, and Ester Yazzie-Lewis

Buy the book from the UNM Press, or Amazon or read the Book Review in Public Health Reports

KM note: This is far from the only book covering the topic of legacy of uranium mining. Yellow Dirt, Wastelanding, and Uranium Frenzy all cover the same topic with varying focuses.

Website: EPA overview of Abandoned Uranium Mines (AUM) on the Navajo Nation

The official website of the status of AUM cleanup: https://www.epa.gov/navajo-nation-uranium-cleanup.

Notable pages and documents include

- The most recent federal action plan, released in 2020

- Contaminated Structures Fact Sheet, which describes one of the most significant risks to human health, structures and homes built with abandoned ore and waste rock

- Safe Drinking Water, which details the risks of consuming water conaminated with uranium. Recently, it was estimated that approximately 15\% of the residents of Navajo Nation did not have piped water in their homes, down from about 30\% in 2003.

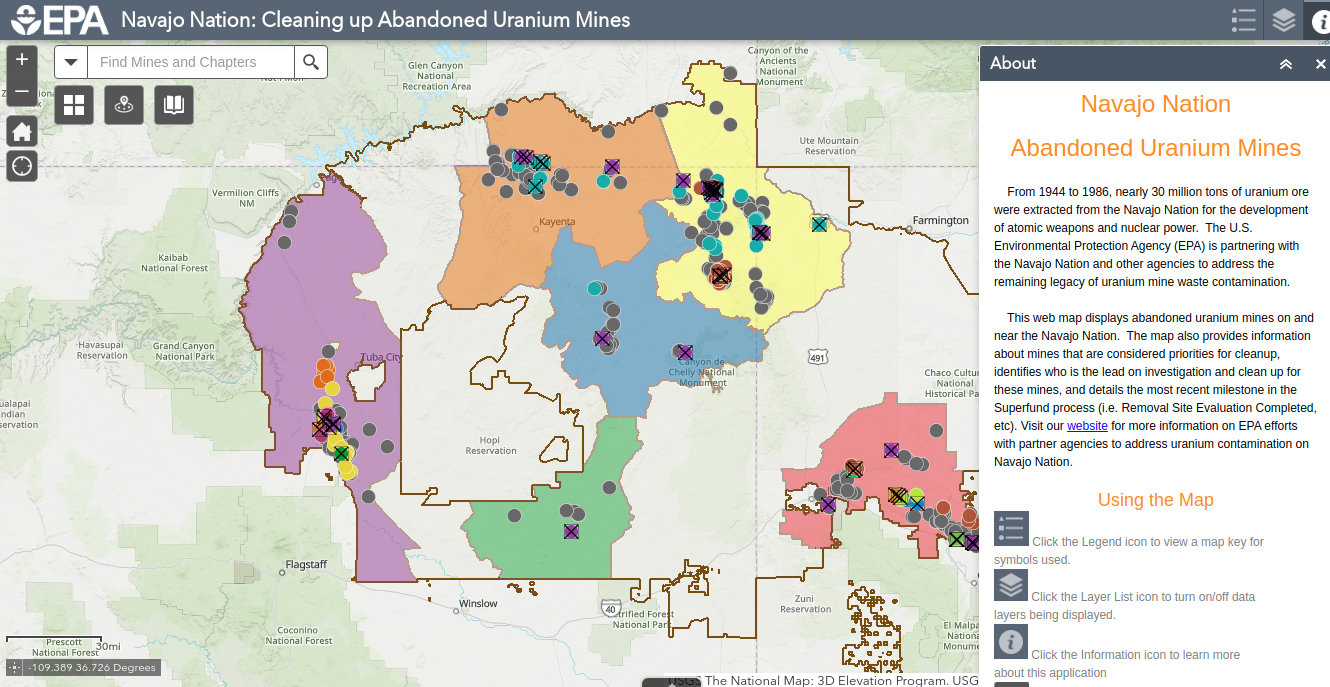

Map: Abandoned Uranium Mines on and near the Navajo Nation

Interactive map maintained by the EPA. Key features include a locator for “mines near me”, coloring based on mine ownership, and marks denoting priority mines.

Early Low-Level Waste Disposal Sites

Maxey Flats Disposal Site, Kentucky.

In 1963, the state of Kentucky and Nuclear Engineering Company (Now US Ecology) opened a low-level radioactive waste disposal facility in Kentucky, placing material in unlined trench and covering the material with soil that eventually collapsed into the ditches as void spaces between waste packers filled with soil. Water began to pool in the trenches and eventually needed to be pumped of of the trenches. In 1977, it was discovered that the leachate was migrating through the ground. Tritium, a particularly mobile radionuclide, was detected in surface water, ground water, and vegetation. Maxey Flats became a Superfund (CERCLA) site.

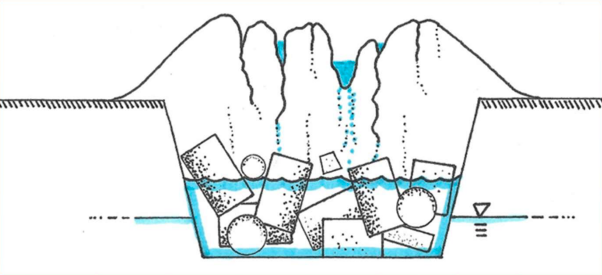

The “bathtub” effect. Image from W. Roy lecture on Low-Level Radioactive Waste Management.

Maxey Flats as well as another low-level waste disposal facility in Sheffield, Illinois, were managed by placing impermeable covers over the trenches rather than the much more expensive process of exhuming the site and reburying the millions of cubic feet of material. In the case of Maxey Flats, the EPA expects to monitor the site for at least 100 years, and perhaps in perpetuity.

Fact Sheet and Website: Maxey Flats, Kentucky, Disposal Site from the EPA office of Legacy Management

EPA’s official Fact Sheet and Project Website. The most recent review was published in 2017, noting that remediation is complete but institutional controls and monitoring will be in place for at least 100 years.

DO NOT DIG OR DRILL sign at Maxey Flats. From the EPA’s 2017 Five-Year Review of the site.

Website: Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet Superfund Branch site on Maxey Flats Section

Project summary and documentation. Reports up until 2017. Website

Conference Article: Final Closure of the Maxey Flats Low-Level Radioactive Waste Disposal Site

In Waste Managment Symposia, 2016

Journal Article: Kentucky’s “Atomic Graveyard”: Maxey Flats and Environmental Inequity in Rural America

By Caroline Peyton, lecturer of social sciences at Cameron University [now lecturer at University of Memphis]. 2017. Light on science, heavy on storytelling. Available (need instiutional access) through JSTOR, and may or may not be available on sci-hub, whos to say? ¯_(ツ)_/¯

Textbook Chapter, Geologic Problems at Low-Level Radioactive Waste Disposal Sites

By John Robertson of the USGS, in Groundwater Contamination. 1984. Available for free from the National Academies Press

Disposal of 55 gallon drums at Sheffield. Image from W. Roy lecture on Low-Level Radioactive Waste Management.

Addendum: Textbooks of Potential Interest

Radioactive Waste Management in the 21st Century

If you’re interested in learning more about the science and practice of radioactive waste management, I would highly recomend pre-ordering Radioactive Waste Management in the 21st Century (release date July 2021). It is authored by geochemist and professor/lecturer at the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign, William Roy.

Much of my own knowledge and passion for radioactive waste management arose from his courses and mentorship, and I still refer to his lectures for material that is inaccessible elsewhere on the web. Professor Roy was also the first to spark my interest in the fate of early low-level radioactive waste disposal efforts.

Preorder availalbe from World Scientific, Amazon, Barnes and Noble.

$48 Paperback, $98 Hardcover.

Equity Issues in Radioactive Waste Managment

Edited by Roger Kasperson, a professor and expert in risk communication who pioneered the theory of social amplification of risk (I have several of his papers close on hand in my Zotero). 1983. Not many copies laying around, although you may be able to find it in a university library. A few used copies are for sale on Amazon and AbeBooks

This wide-ranging textbook covers equity issues such as labor, intergenerational planning, and siting. The chapters balance nuclear science with social science, and although the book is just shy of 40 years old, I find it engaging and relevant, although not every recommendation has withstood the test of time.

* My esteemed panelists are listed below

- Isabelle Boemeke, Nuclear Energy Influencer. Instagram, Twitter, News Coverage

- Josh Freed, Senior Vice President, Climate and Energy Program, Third Way. Twitter

- Kirsty Gogan, Co-Founder, TerraPraxis, and Managing Partner, LucidCatalyst. Twitter, Appearance on Titans of Nuclear

- Rich Powell, Executive Director, ClearPath and ClearPath Action. Twitter

Comments