Using precise and accurate terminology is not always the most important thing when you’re, say, shitposting on Twitter, but I’ve noticed there is frequent confusion online about the term isotope, and exactly what it refers to. Also, what is a nuclide and when should you use isotope vs nuclide?

Of course, no one is going to force you to use the correct terminology unless you’re in the process of learning or conducing nuclear physics/engineering/science, but if you want to sound like you Know What You’re Talking About, here is a quick guide.

Last updated 1/15/22 Grammatical edits. Revisions to clarify language based on feedback. Also I added some more details about the cool science of isotopes, but I won’t be hurt if you skip it since I did promise this to be a “short” guide.

Nuclide

Nuclide is the umbrella term for “atoms that have some number of protons and neutrons”. An easy way to grasp it is to envision the word nuclide as a nuclear version of the word element. Element, as many remember from long-ago chemistry lessons, refers to atoms that are defined by a fixed number of protons. Carbon is an element, and it always has six protons. If you add or remove a proton from carbon, it is still an element, but it is no longer carbon. 5 protons means boron, and 7 means nitrogen.

In chemistry, one typically cares only about the element (protons) and how many electrons an atom has, which determines its chemical properties.

In nuclear science however, the number of neutrons is important as well as the number of protons and electrons. When the nuclear properties matter (they don’t always), and you just want to talk about some number of atoms of unknown or variable element, you would call them nuclides. Some nuclides you’ve probably never heard of are cerium-122 and holmium-177, because I just randomly found them online. It’s ok if you’ve never heard of the elements, either.

If you want to talk about radioactive atoms, but your conversation is not necessarily limited to a single element, those would be radioactive nuclides, or radionuclides. A few examples of radionuclides:

- uranium-235, which has 92 protons and 143 neutrons

- hydrogen-3, which has 1 proton and 2 neutrons. It is often referred to as tritium

- carbon-14, which has 6 protons and 8 neutrons. This is the type of radioactive carbon important for carbon dating of organic material, along with the non-radioactive carbon-12

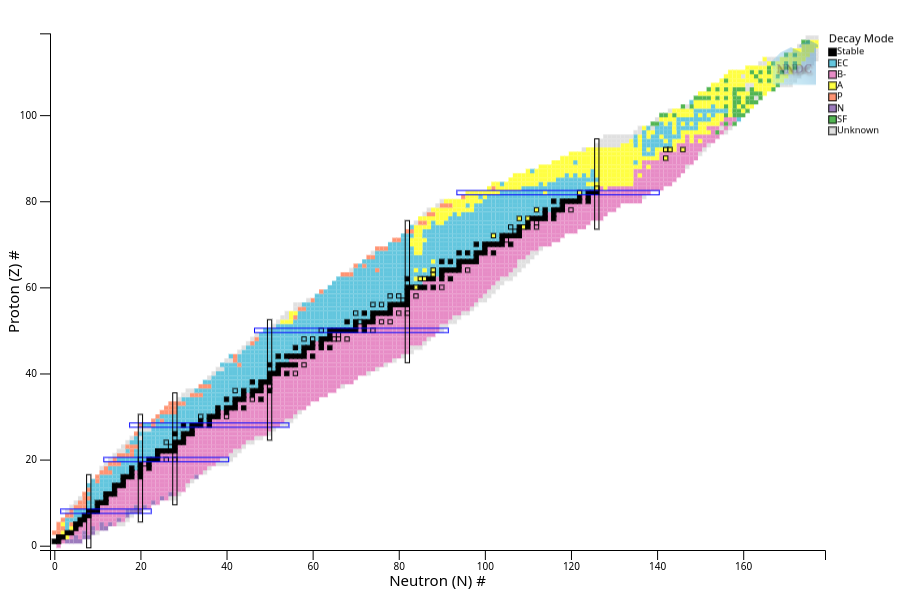

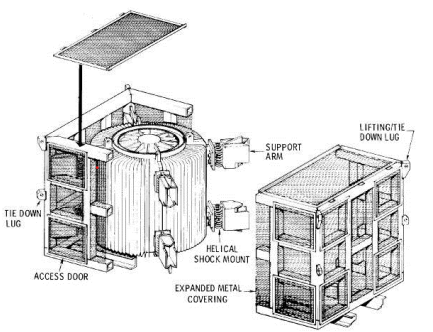

Aside: the Chart of the Nuclides

Just like there is a periodic table to visualize the elements, there is a nuclear version to visualize all the nuclides. It’s called, somewhat more dryly, the Chart of the Nuclides.

It looks a bit intimidating, partly because it’s huge, but the concept is actually rather simple. First, stretch the periodic table so every element is stacked on top of the previous element, along the Y axis. No more rows based on chemistry! Neon (10 protons) goes right below sodium (11), even though they’re not next to each other on the periodic table.

All types of hydrogen have a y value, or Proton number, equal to 1. Helium, y=2, and so on.

Then add a second axis of neutron number. Regular ole hydrogen with zero neutrons, has a box at (0,1). Hydrogen with one neutron, but still one proton because that’s the definition of hydrogen, is (1,1). And so on and so forth. When you put every nuclide known or produced onto a (x,y) aka (neutron/proton) chart, this is what you get.

Chart of the nuclides, colored by type of radioactive decay. Only the black boxes are stable nuclides. Probably fewer than you thought, huh? Image from NuDat of Brookhaven National Lab’s National Nuclear Data Center. I also really like this 3D chart of the nuclides by Ed Simpson

You can buy the Chart of the Nuclides as a book or giant poster from the US Naval Nuclear Labs. They’re not that expensive, and I strongly encourage anyone to join the “nuclear science decor is cool” camp. I’ve had one hanging in my living room for many years, so I have a vested interest in convincing people that it is a “cool thing to do”.

…ok, so what’s an isotope?

Isotope is used to specify a nuclide (using the new vocab word right away!) of a specific element. For example, if we’re only talking about uranium, then we can talk about isotopes of uranium. The isotope uranium-235 has 3 fewer neutrons than uranium-238.

U-235 and U-238 are isotopes of uranium, but they’re not the only isotopes. Not even the only naturally-occurring isotopes of uranium in greater than trace quantities, we would be gently reminded by uranium-234 if it was anthropomorphized. They’re also nuclides, but calling them isotopes reminds us they are the same element and have the same number of protons.

Conversely, uranium-235 and plutonium-239 are not isotopes. They are different elements, with uranium always having 92 protons and plutonium always having 94. Nuclides!

Self-check: Are all isotopes nuclides? Are all nuclides isotopes? Think about it, and see the answer at the bottom of the page

Another common mistake is assuming that nuclides or isotopes are the same as saying radionuclide or radioisotope. Carbon-12 and oxygen-16 are nuclides, and they’re not radioactive. Hydrogen-1 and hydrogen-2 (aka deuterium) are isotopes of hydrogen, and they’re both stable too.

Science time? Science time!

Using the word nuclide or isotope generally means that the properties of the nucleus, or nuclear properties, are important to the story for some reason. Hydrogen-1, or protium (but who calls it that?) and deuterium are not radioactive, but they have different nuclear properties. Which one you put in your nuclear reactor is really important because it affects neutronic behavior. Keep that in mind next time you build yourself a nuclear reactor, will ya?

There is another major use of isotopes that nuclear engineers often forget to mention (because we’re not a part of it, usually), and I thank biochemist Michaela Pereckas for gently reminding me of this fact after I hit publish.

The mass difference, and/or the difference in radioactive half-lives between isotopes (“of the same element” is implied by using the word isotopes instead of nuclides) is exploited to do very cool science in a wide variety of fields, from climate science to biochemistry to geology and archeology. And, these fields use a wide variety of nuclides to do it! (different elements, and a mix of radioactive and stable nuclides)

You’ve probably heard of one technique, carbon dating, which compares the ratio of radioactive carbon-14 to to stable carbon-12 to determine the approximate age of an object, at least until all the carbon-14 decays away.

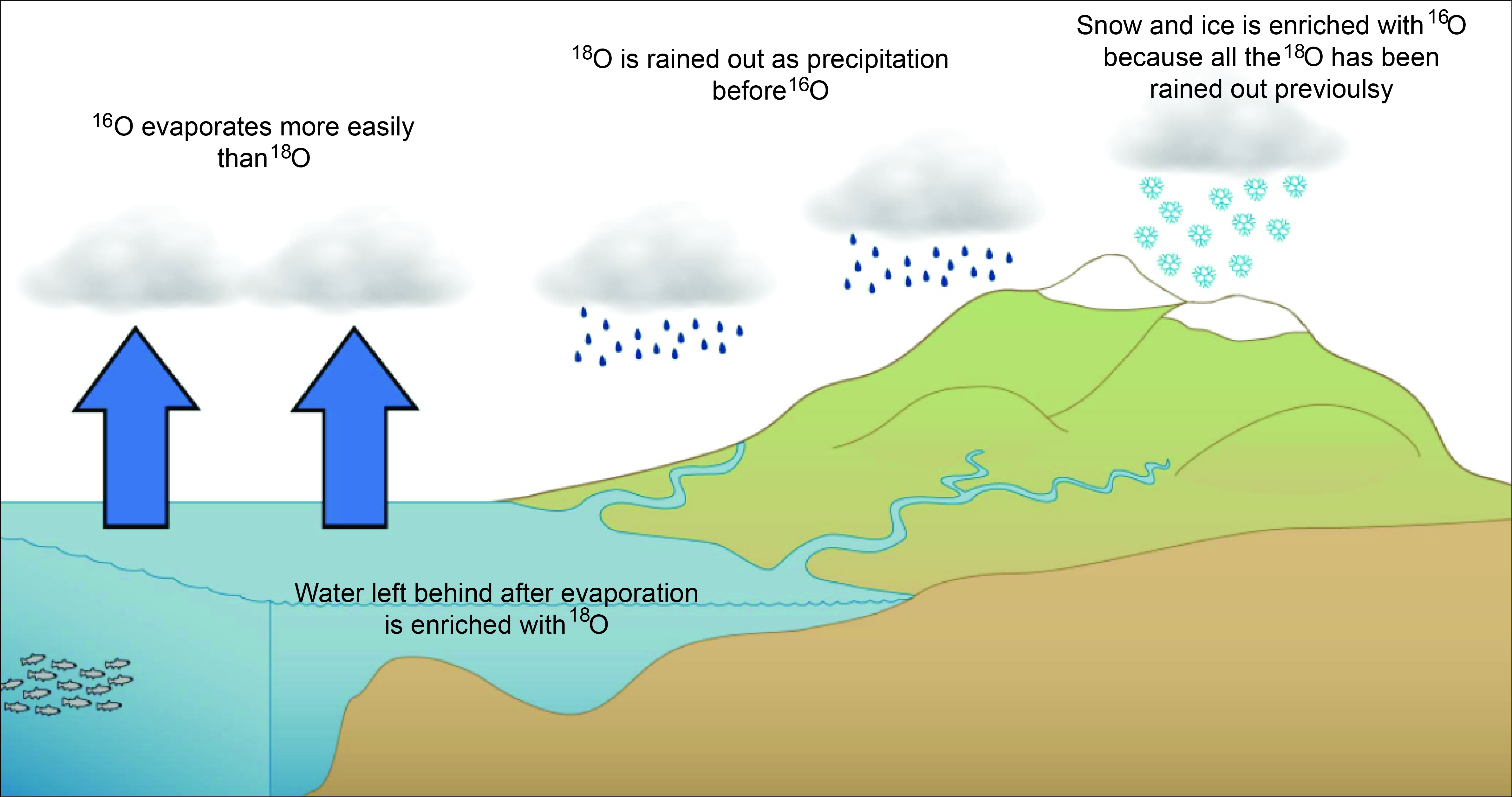

Another fascinating example is in paleoclimatology, where scientists can study the ratios of two stable isotopes of oxygen, oxygen-16 and oxygen-18, to study long-term changes in the Earth’s climate.

Although O-16 and O-18 are not radioactive and have the same chemical properties, they have a tiny difference in mass. The weight of two neutrons is quite small, but enough for heavier oxygen-18 to be affected by gravity just a little bit more than oxygen-16.

When water evaporates from the oceans, it is slightly enriched in the lighter oxygen-16. This process compounds when precipitation pulls the heavier oxygen-18 back down to the surface at a slightly faster rate as clouds move from the warmer regions near the equator towards the poles. Gravity at work!

From Time Scavengers, which in turn modified it from Silent Witnesses/Emma Versteegh

From Time Scavengers, which in turn modified it from Silent Witnesses/Emma Versteegh

During times of glacial expansion, glaciers build up using water enriched in oxygen-16, leaving the oceans depleted in oxygen-16, which is the same as saying enriched in oxygen-18 since we’re only discussing two isotopes. Oxygen-17 exists, but we ignore it here because there is a lot less of it. Just like nuclear engineers often ignore the existence of uranium-234 (sorry, not sorry).

Anything using water from the oceans during glacial expansion periods, depleted in oxygen-16, will also be depleted in oxygen-16. The opposite is true too. Water not depleted in oxygen-16 from times of glacial melting/no glacial expansion will leave this mark on the world interacting with the oceans at that time.

Before this turns into a climate science blog, let’s skip to the end. Scientists can study the ratio of oxygen isotopes in shells, ice cores, ocean sediments, and more to learn about the climate from when those materials lived/were formed. Isotope science ftw!

If you’re thinking that words like “enriched” and “depleted” sound a lot like words you may have heard about uranium for nuclear reactors, you’re spot on. Uranium enrichment is like long-term oxygen evaporation trends in the sense that it is the mass difference of two isotopes that is used to create a product that has a higher ratio of one isotope relative to another. We enrich uranium-235 and accordingly deplete uranium-238 to obtain appropriate isotopics for the kinds of nuclear reactors we use in the U.S.

There are other terms relating multiple nuclides to each other based on nuclear properties, including isobars, isotones, and isomers. These pop up in the media far less frequently, so just google them if you’re curious.

Thanks for this, but why?

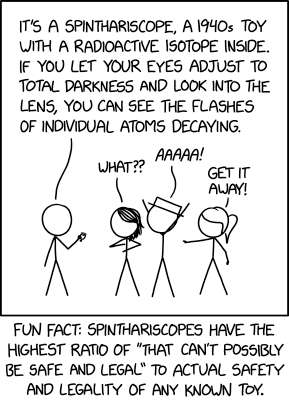

It’s a rare day when I actually get to be pedantic about an xkcd comic. Randall Munroe usually does a fantastic job when weaving nuclear science into comics, but in this case he just happened to stumble into the trap of an extremely common mistake. Comic 2568 uses isotope when the element is not specified or fixed, and should instead be nuclide.

Spinthariscopes, a neat tool to visualize radiation that are almost as old as our knowledge of radioactivity itself, were historically made using radium as the radionuclide, but modern versions generally use americium-241 or thorium, such as the one available for purchase at United Nuclear.

Thorium has multiple naturally occurring isotopes, but it is very overwhelmingly comprised of thorium-232. I admit that thorium-230 exists as a higher fraction of natural thorium than uranium-234 does for natural uranium, but for nuclear engineers it’s common practice to omit the mass number (protons plus neutrons) because we mainly pretend it’s all thorium-232. I got a comment from geologist Lynne Elkins about not mentioning this in an earlier draft, because you can do science with thorium-230, but I have a nuclear engineer hat on so I made the common nuclear engineer mistake of pretending low-fraction isotopes you don’t care much about don’t exist :)

Does this really matter?

Well, it depends of how you define “matter”. If you like sounding pretentious and/or care about your words being correct, then yes. If you just want your nuclear science explanation to be understandable to others, then it might not really matter, usually.

I rarely see an online definition that is just wrong, but it is fairly common for even nuclear engineers to call americium-241 a radioisotope, even when they’re not comparing it to another isotope of americium but just describing it on its own. Or, even describing its spontaneous fission rate relative to a nuclide of another element! But their meaning is clear, so does it matter?

This conflation of squares and rectangles has even seeped into technical jargon in the field. Radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) can use plutonium-238 or strontium-90 (among other possibilities), but they’re generally not called radionuclide thermoelectric generators. Radioisotope identification devices don’t presume to know the element beforehand, they’re used to identify a radionuclide even if little prior information is available.

Sighing gently, I will conclude that this doesn’t actually matter that much. But it’s fun to know the correct term, and I expect you think so too since you’ve made it this far?

To Summarize

If you’re talking about a single element:

- isotope(s)

- radioisotope(s) if you know it’s radioactive. Or radioactive isotope, which some people prefer

If you are talking about multiple elements, or you don’t have enough info to know for sure:

- nuclide(s)

- radionuclide(s) if you know it’s radioactive. Or radioactive nuclide, it’s the same thing

If you don’t really care:

- fine, say isotope, I can’t stop you! I might shake my fist at you, but that’s all I can do!

Self-check answer: This is like squares and rectangles. Isotopes are to squares as nuclides are to rectangles. All isotopes are nuclides, but not all nuclides can appropriately be described as isotopes, and it depends on the element(s) being described.

Isotope is simply a more precise way to describe nuclides, when they are the same element. If you’re not sure, you can always default to nuclides, the umbrella term.

Comments