This is the general audience chapter of my dissertation. It was written as part of the Wisconsin Initiative for Science Literacy (WISL) Communicating PhD Research to the Public project. The original pdf version of this chapter can be found on the WISL website, along with many similar chapters across a number of scientific disciplines, or on the PhD page of my website.

Science is only useful when it is communicated. Scientific journals and conferences propagate advancements within a discipline and allow scientists to build on each other’s work. Events with schools help grow the next generation of scientists, and I can trace my own journey back to science summer programs and opportunities to meet scientists as a kid. General audience media is for everyone to enjoy and explore the new knowledge and capabilities generated each day by scientists and engineers.

For many scientists, however, only the first type of communication counts as part of their jobs unless they can convince high-profile organizations like

Nuclear engineering has a long and complex relationship with public communication. When the fields of risk communication and decision science were first being developed, nuclear energy, nuclear waste, and nuclear weapons were consistently studied as examples of industrial hazards.

After the Three Mile Island accident in 1979, the nuclear power industry learned to communicate its operational experience across companies (a very good practice that continues today) and to limit its communication to the public to avoid potential communication mishaps (a bad practice that is still being unlearned). The limited public communication strategy backfired, allowing entertaining but not factual portraits of nuclear power like The Simpsons and anti-nuclear energy activists to dominate the information ecosystem. The lack of public presence has contributed to the spread of misperceptions and a general lack of awareness of nuclear energy compared to other energy sources. Nuclear engineering has always needed messengers. Here is my story as a nuclear engineer and the story of my dissertation.

tl;dr

Over 180 countries have signed the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons1, promising never to develop nuclear weapons. We don’t just take them at their word, though. In signing the treaty, each country agreed to declare their nuclear materials and facilities and open them up for inspection to an independent agency within the United Nations system, called the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). My dissertation enhances the capabilities of a computer code called Cyclus, which models the movements of nuclear materials throughout their entire lifecycle, to support this verification system.

I demonstrated the ability of Cyclus to “play nicely” in the international safeguards verification system by incorporating an analysis technique that’s already used in the field into the Cyclus ecosystem. I dug into the way that nuclear facilities in Cyclus trade nuclear materials between them, adding new capabilities that replicate more complex behavior and overcome prior limitations. I created a tool to convert those simulations into synthetic nuclear material accounting reports using the exact format that countries have to use when they submit their reports to the IAEA. Finally, I created a small set of fake countries that can be used for demonstrations of realistic nuclear material movements without being limited by what exists today.

Together, these capabilities can be used to create synthetic versions of nuclear material accounting reports, which real countries use to record detailed information about their nuclear materials. These synthetic reports can be used to find more efficient ways to implement the IAEA’s inspection system, especially useful now with the agency having a strained budget and increasing number of nuclear facilities to inspect. They can also be used to look for previously unknown signatures of nuclear material diverted away from peaceful uses towards a potential nuclear weapons program.

Introduction

I’m part of a global hide-and-seek game, where the stakes could not be higher. Any time a new country develops nuclear weapons, the potential for accidental or intentional use increases.

Let’s call any country that wants nuclear weapons the hider. I don’t know if or how many hiders even exist. If any do, they have access to an entire nation’s resources to stay undetected. I use the analogy of a kid’s game, but in the real world, this is deadly serious. Any hiders do not want to be found.

Who are the seekers? Well, anyone who doesn’t want additional nations with nuclear weapons to exist as a start. But more specifically, the IAEA. This organization is affiliated with the United Nations and tasked with enforcing the provisions of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT)1. Nearly every country in the world is a member of the treaty, which places each signatory nation into one of two categories: nuclear-weapon States, and non-nuclear-weapon States. The IAEA calls countries/nations States with a capital S, which is the terminology used through the rest of the dissertation, but I’ll stick with countries here.

In this analogy, I’m not a seeker, I’m more like the seeker’s support team. My goal is to find new ways to seek out clandestine nuclear activities. I’m building software that enables researchers to play virtual hide-and-seek, where they get to act as both sides of this adversarial game. By simulating many hypothetical hide-and-seek games, we can hopefully make it easier to detect potential real-life secret nuclear weapons programs.

So how does one end up getting a nuclear engineering Ph.D. in nuclear nonproliferation?

I mentioned that my work is designed to help detect the spread of nuclear weapons technology. We’ll return to the story later, there’s a lot more to tell. But right now, I want to share with you how I ended up here.

As a kid, I fell in love with the mountains. My dad’s family is from central Pennsylvania, in the heart of the Appalachian Mountains. We would visit them every year. Those mountains are old, older than anything humans can really wrap our minds around. They’re a product of immense geologic forces. Every mountain stands in defiance of the gravity, wind, and water that seek to pull them back down. I was, and am, awestruck.

These dominating and yet delicate landscapes drew me to a passion for the environment as I grew older. I wanted to study natural systems, I thought. I wanted to be a meteorologist or an astrophysicist. Maybe a geologist studying water systems? I learned that mountains, like every other ecosystem on our planet, are affected by climate change, which spurred my passion even more.

Then, I learned about engineering and decided that I could channel my energy into climate solutions. I could use the power of applied science to protect the natural systems I loved. My attention eventually fell on energy, which powers our modern life. The widespread adoption of electricity, much of it generated from burning coal and other fossil fuels, has enabled many of our technological advances in the past century. Of course, it has also pumped enormous amounts of carbon and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

I believe that we need to build a future that doesn’t emit carbon but also allows the entire world to reach the living standards we enjoy in the United States. We need a world powered by clean energy. I sought information about solar, wind, hydro, geothermal, and nuclear energy.

I now know that all kinds of engineers work on climate solutions. But as a 17-year-old, it made sense to pursue a major that was such an obvious pathway to work on clean energy: nuclear engineering. I was lucky to find mentors and role models who helped me see nuclear energy and engineering as a viable degree and career for myself.

It turned out to be a perfect fit for me. Nuclear engineering is very physics-heavy for an engineering field, letting me satisfy my childhood dream of studying complex scientific systems. The field holds so much promise, but there are also many challenges to overcome. I didn’t want a slam dunk.

As an undergraduate student, I discovered that I had a passion for interdisciplinary challenges. I loved the pure science and the engineering of my classes, but I was drawn to the socio-political aspects of nuclear energy and engineering in the real world.

It wasn’t until the summer after I got my bachelor’s degree that I even really thought about nuclear weapons. Nuclear engineering programs train students specifically for careers in nuclear energy or in medicine. Nuclear technology has so many incredible peaceful uses. Although it’s common for people to assume that nuclear power plants can blow up like an nuclear bomb, the technologies are designed very differently; even the worst possible nuclear accidents could not cause an explosion like a nuclear weapon. Undergraduate nuclear engineering students are not typically taught about nuclear weapons proliferation or the prevention of nuclear weapons proliferation through nonproliferation.

Nuclear nonproliferation only became a focus of mine when I came to Los Alamos, New Mexico for the first time as an intern at Los Alamos National Lab (LANL). I studied the use of nuclear thermal rockets for space power, but I also learned nuclear history. Known as the birthplace of the atomic bomb, Los Alamos played a pivotal role in the Manhattan Project (have you seen Oppenheimer?).

“Nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought”. U.S. president Ronald Reagan and then-Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev made this statement in 1985, and it’s still powerful, and true, today. It is so important that the five nuclear-weapon States signatories of the NPT, the U.S., France, U.K., Russia, and China have recently released a joint statement re-affirming the phrase.

That summer, I learned about the NPT. I learned that the IAEA is still checking to make sure that countries that signed the treaty as non-nuclear weapons States are holding up their end of the bargain. And I found a way to think about climate change and nuclear weapons together as two existential threats to humanity.

I joined the hide-and-seek game.

The uranium lifecycle

My work brings together two different applications of nuclear engineering that have historical overlap but have long since diverged. I’ll introduce them separately and then tell you how I brought them together and what my work enables.

Although I bridge two disciplines, I consider myself first and foremost an expert in nuclear fuel cycle modeling. The nuclear fuel cycle is a technical term for the lifecycle of nuclear materials like uranium. This encompasses all the steps from digging up uranium-bearing ore from the ground to the chemical processing that turns rock into highly refined nuclear fuel assemblies, to the reactor itself, where uranium is split in two by a process called nuclear fission, to the final permanent disposal of nuclear fuel back underground.

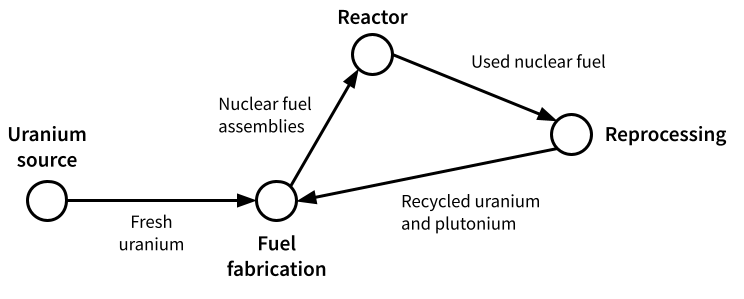

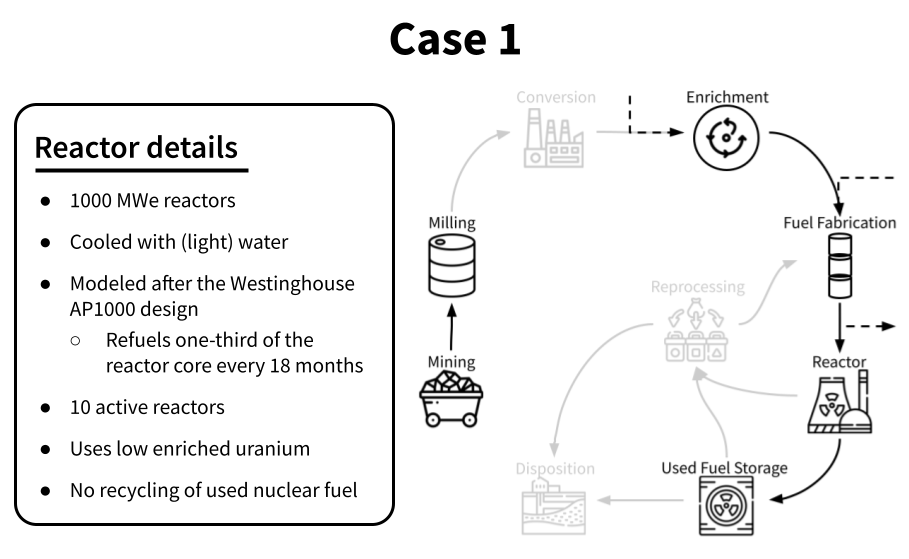

![]() The nuclear fuel cycle starts with mining of uranium and/or thorium and ends with disposal of nuclear materials. Reprocessing can be used to recycle used nuclear fuel for additional use in a reactor, which is called a closed nuclear fuel cycle. Otherwise, the fuel cycle is called open.

The nuclear fuel cycle starts with mining of uranium and/or thorium and ends with disposal of nuclear materials. Reprocessing can be used to recycle used nuclear fuel for additional use in a reactor, which is called a closed nuclear fuel cycle. Otherwise, the fuel cycle is called open.

Much of nuclear engineering is focused on the nuclear chain reaction occurring in the reactor core and all the complicated processes that are needed to build and maintain a nuclear reactor and turn the energy from nuclear fission into usable electricity. My work in the nuclear fuel cycle is instead focused on the supply chain of nuclear materials that fuel the reactor and is responsible for the used nuclear fuel afterwards.

I went to graduate school specifically to pursue nuclear fuel cycle modeling. From my earliest days as an undergraduate in nuclear engineering, I was drawn to the complex system that supports energy-producing nuclear reactors.

International nuclear safeguards, the global hide and seek game

At the advent of the nuclear age, in 1945, only one country had nuclear weapons. The United States developed nuclear weapons in the secret Manhattan Project during WWII. The U.S. announced their existence by deciding to drop two nuclear bombs on Japan, killing between 110,000 and 210,000 people depending on the source and their assumptions2.

U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower gave his famous “Atoms for Peace” speech in 1953, leading to the creation of the IAEA as an independent agency within the United Nations family. The IAEA was created to promote peaceful uses of nuclear technology, which are now entrenched in modern life. Nuclear power has produced nearly 20% of American electricity for decades and has avoided over 1.8 million deaths that would have been caused by air pollution if the same electricity had been generated by fossil fuels3. Nuclear technology has also saved millions of lives through the development and use of nuclear medicines, and food irradiation limits the spread of foodborne illnesses and can limit food waste by extending the shelf life of products.

But the nuclear materials used in nuclear energy, like uranium, can also be used in a nuclear weapons program. One of the very first public reports on the potentials of atomic energy, released by a committee of the United Nations approximately one year after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, made this connection explicitly4.

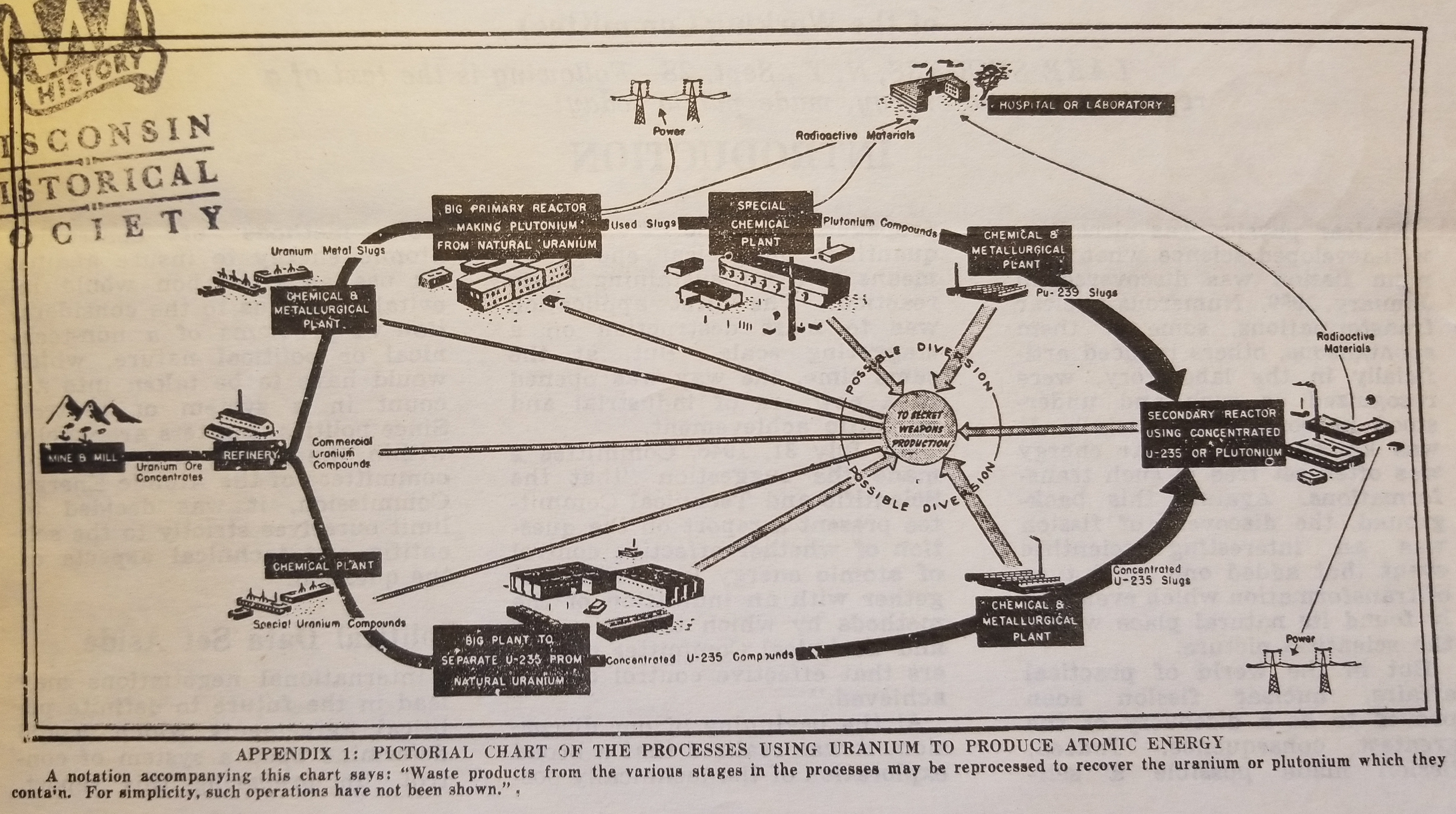

This diagram, produced by the newly-formed Atomic Energy Commission of the United Nations in 19464, is likely one of the first nuclear fuel cycle diagrams ever produced. It notes that every step could possibly diverted “to secret weapons production.”

This diagram, produced by the newly-formed Atomic Energy Commission of the United Nations in 19464, is likely one of the first nuclear fuel cycle diagrams ever produced. It notes that every step could possibly diverted “to secret weapons production.”

By the mid-1960s, five countries had developed nuclear weapons and many more were either pursuing them or considering developing a nuclear weapons program. The U.S. and the Soviet Union led the development of a treaty to limit the further spread of nuclear weapons while explicitly supporting the use of peaceful uses of nuclear technology.

The NPT was a landmark treaty, with several core principles laid out in the individual Articles. Signatories of the treaty were categorized as nuclear-weapon States or non-nuclear-weapon States. The non-nuclear-weapon States agreed not to develop nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices, and nuclear-weapon States agreed not to share their nuclear weapon technology. Everyone agreed to promote and share peaceful nuclear technologies.

And the non-nuclear-weapon States agreed to allow safeguards, defined in the NPT as “verification of the fulfillment of its obligations assumed under this Treaty with a view to preventing diversion of nuclear energy from peaceful uses to nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices.”

This mission of safeguards continues today, with over 180 countries as non-nuclear-weapon States signatories of the NPT. While most of the non-nuclear-weapon States have few nuclear materials or facilities, there are hundreds of nuclear reactors and other fuel cycle facilities under safeguards around the world. For example, large nuclear power programs like Canada’s and South Korea’s have dozens of reactors between them, and there are critical nuclear fuel cycle facilities, like uranium enrichment and fuel fabrication, in the Netherlands and Germany.

All of this verification work, which includes careful evaluation of every nuclear material movement between facilities and inspectors flying around the world to physically assess nuclear materials, must be conducted under a regular budget of about $181.5 million, using the average 2023 EUR-USD exchange rate. This is less than the University of Wisconsin–Madison reported in athletic spending during the 2022-2023 school year.

Given a massive mandate and a limited and stagnant budget, there is a demand for new techniques that help the safeguards process become more efficient while adapting to new facilities and challenges.

My thesis

By the 2000s, work in nuclear fuel cycle simulation had long since diverged from international safeguards. At least informally, the safeguards community perceived that computer codes designed for nuclear fuel cycle simulation were not detailed enough to be useful.

As an early grad student, I started attending conferences on nuclear nonproliferation and introduced myself and my background in nuclear fuel cycle modeling. I was met repeatedly with the perception that the codes that I worked with were not useful and that previous efforts were undereducated in safeguards.

Part of this challenge is the vastly different time scales on which long-term nuclear energy planning and international safeguards operate. The former considers decades, even centuries, into the future and can, therefore, oversimplify what happens on a day-to-day level. The latter is tasked with identifying signs of nuclear material diversion as quickly as possible and is concerned with the patterns of nuclear material movement each day and month.

This skepticism motivated my first project, which was designed specifically to demonstrate how a nuclear fuel cycle simulator could be used within the existing techniques of international safeguards.

Meeting the field of international safeguard where they are

The first project of my dissertation takes an existing methodology developed by the IAEA, acquisition path analysis, and implements it within the ecosystem of a nuclear fuel cycle simulator. This work was meant to show that not only could we use the flexible nature of Cyclus to replicate an existing technique, but that there were opportunities to further advance the technique using specialized capabilities for modeling the movements of nuclear materials that are available within Cyclus.

Acquisition path analysis looks at all parts of the nuclear fuel cycle and simplifies them down to a mathematical model called a graph, where all of the facilities are called nodes, and the nuclear materials that could be traded between them are edges that connect the nodes.

This graph theoretic representation is a very common technique in mathematical modeling. Graphs are used to represent all kinds of systems. A familiar use of graphs is social graphs created by social media. You and your friends on a social media platform can be represented as a graph; each individual person is a node, and the edges represent the connections between you and another person.

In the most basic type of graph, edges are bidirectional. There’s no to or from, both ends of the edge are the same. However, when edges represent nuclear material flows, they are directional. There is a place where the nuclear material comes from and a place where it goes to, like an arrow rather than a line.

A social media graph can go either way. On Facebook, the connections, called “friends”, are mutual. Regardless of who sends the request and who accepts it, friendship goes both ways. Platforms that use followers are directional, such as X/Twitter, Bluesky, and Instagram. On these directional graphs, someone you follow is an edge that goes from you to them, and then if that person follows back a second edge goes from that person back to you.

A directional graph. If the nodes were people instead of nuclear facilities and the edges were directional follows, this would be a would be a weird love triangle.

A directional graph. If the nodes were people instead of nuclear facilities and the edges were directional follows, this would be a would be a weird love triangle.

This directional graph, or digraph, is the type of graph that we use to represent the nuclear fuel cycle. After carefully setting up nuclear facilities and nuclear materials that should be in your graph, my tool uses analysis techniques to generate several metrics of interest. The famous “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon” game of acting in Hollywood is an example of a metric from a graph where the nodes are people, and the edges represent the two actors acting in the same movie or show. How many steps connect Kevin Bacon and another actor is a type of metric.

Some of the metrics in my tool include the number of different ways to produce nuclear materials of interest, the shortest path to those materials, and which paths loop back on top of themselves, called cycles.

The tool I created to conduct acquisition path analysis was a great first step to demonstrate a system that could be deployed in an international safeguards context. I presented my work, including a live demonstration of an interactive tool, at the same conference where I had previously experienced skepticism at the usefulness of nuclear fuel cycle simulators. I won first place in the student paper award.

However, I ran into a problem. There wasn’t additional information available about where to take my tool next, what new metrics would be helpful to the IAEA. This lack of information would be great for some researchers but not for the highly applied nature of international safeguards.

Consider research in science and engineering as a continuum from basic to applied. I don’t mean basic as in simple. I mean basic as in fundamental, studying the core properties of a system. Think about some famous scientists you’ve heard of, they are all likely people who studied basic science. The intellectual lineage of nuclear engineering is built on the basic science that Marie Curie did to identify the principles of radioactivity and discover the elements radium and polonium.

The other end of the spectrum is typically categorized as engineering, where the basic principles of science are applied to a system to build something or do something with a specific purpose. The field of international safeguards is at the far end of the spectrum on the applied side. The goals are very specific and connect back to the NPT and the mission of the IAEA to promote the spread of peaceful uses of nuclear energy while “supporting global efforts to stop the spread of nuclear weapons”.

Any research in international safeguards has a single specific customer: the IAEA. Unlike basic science, research is driven by a clear need, a specific way to apply the new results, technique, or tool being developed. Any new tool or capability must lie within the bounds of the NPT, and all the agreements between individual countries and the IAEA that dictate the details of safeguards implementation.

When I got into international safeguards, I started to hear quips about how university students kept coming up with new ideas, methods, and tools that were novel and warranted a master’s degree or Ph.D., but they weren’t useful. They didn’t solve any real problems. Or, they could not be applied to a real system because they didn’t understand the needs and limitations of the international safeguards system.

Once I had replicated the technique of acquisition path analysis using the open literature available to me, I ran into a situation where I was concerned that if I went further and came up with something novel I would become another one of those students who did interesting work that was ultimately doomed to live on a shelf, because there was not enough information available about how to further develop the technique in a meaningful way.

Instead, I wrapped up this tool, called it a prototype, and recognized that I had met my goals. Not only had I replicated the technique within a field cycle simulator, but I had also clearly caught the attention of the community and demonstrated that this type of computational tool, the nuclear fuel cycle simulator, has great promise.

Around this time, I was also given an opportunity to come back to a U.S. National Laboratory, where I had interned before, to work on projects that were already funded by international safeguards, where I could apply my expertise. So, I made a pivot, and I picked up some new work that either became or inspired all of the other parts of my dissertation. I packed up and moved to northern New Mexico to continue my research at LANL.

Refocusing Cyclus capabilities on the needs of international safeguards

I came to LANL to work on a project to recreate accounting reports for nuclear material, which I believed could be done using the Cyclus nuclear fuel cycle simulator. These reports are something that all non-nuclear-weapon States must regularly submit with information on their nuclear material, location, composition, and movement.

The IAEA created a format for these accounting reports, and I developed a tool that could take a simulation of a country and create synthetic versions of those nuclear material accounting reports. But while doing that, some limitations of Cyclus arose. These limitations were critical for international safeguards and had to be addressed.

This was reinforced by a meeting I had at the time with somebody who knew how this tool would be applied if it ever got transferred to the IAEA, and her reaction immediately identified some of these deficiencies in our modeling capabilities, pointing out that our tool couldn’t be useful if we didn’t address these shortcomings. So, I set out to develop several new capabilities that had to be added to the Cyclus software.

Cyclus was designed to be very flexible to enable a wide range of nuclear fuel cycles to be simulated. It comes with a set of “stock” models but also allows users to connect their own nuclear facility models. This is similar to creating and using DLC, or downloadable content, in video games that allows users to expand the world that the game developers created.

My new capabilities specifically target the way that these nuclear facility models interact with the Cyclus core system, which is a market for nuclear materials. In the simplest sense, a facility takes in some type of feed material from another facility and produces some sort of product that it wants another facility to take off its hands. In between those two steps are the chemical and nuclear process models.

Recent research had mostly focused on improving the process models, such as a nuclear reactor model. My own research early on in grad school included being part of a team that created a better uranium enrichment facility model than the stock option. But there had been almost no corresponding improvement in the ways that facilities requested their feed or supplied their products to the rest of the system.

So, I added new inventory management capabilities. In keeping with the ethos of Cyclus, I created a generic set of new capabilities that are flexible and able to be used across many different types of nuclear facilities. Some are simple, like adding the notion of a regular production cycle where facilities are sometimes active and sometimes dormant, simulating a weekend or a clearing or refurbishment period. Some are more complicated, incorporating random numbers or requesting inventory in specific amounts, using algorithms similar to ones used to stock goods in a store.

On the product side, I added the notion of nuclear material packaging to Cyclus. In the real world, nuclear materials have very strict international regulations on how and in what quantity they can be moved, and this new capability allows nuclear fuel cycle simulations to capture those patterns.

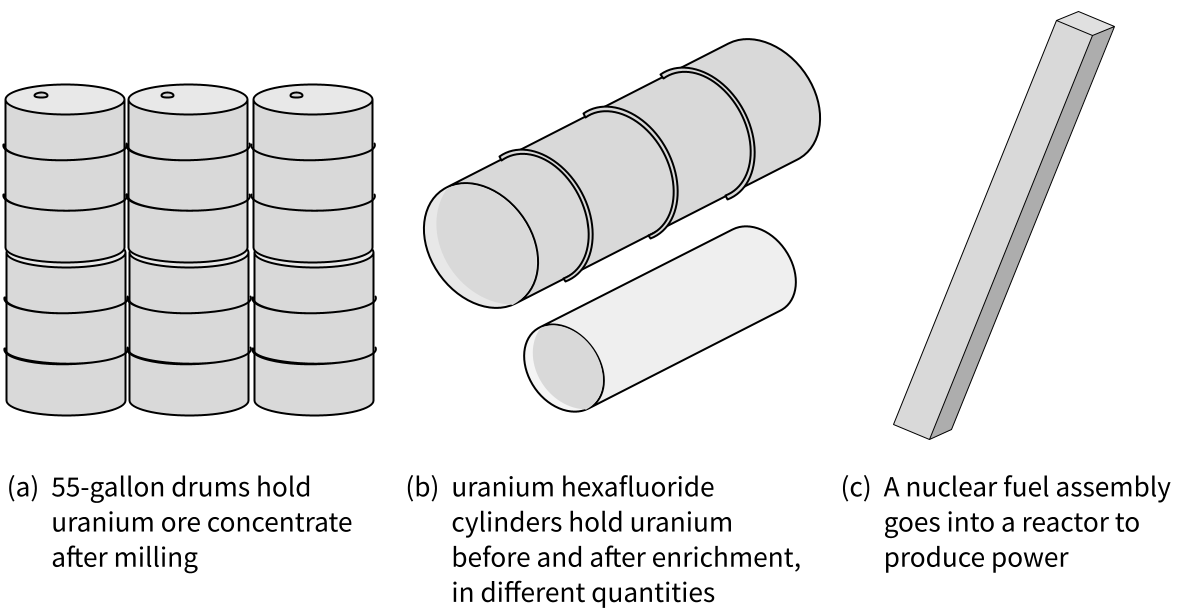

Adding packaging capabilities in Cyclus allows nuclear materials to be represented in realistic quantities, in addition to the realistic chemical compositions they were already modeled as. Here are a few nuclear material packaging types.

Adding packaging capabilities in Cyclus allows nuclear materials to be represented in realistic quantities, in addition to the realistic chemical compositions they were already modeled as. Here are a few nuclear material packaging types.

This work is a story of dozens of small updates to the Cyclus computer code that are each flexible and widely applicable rather than one big flashy new capability. In some ways, that idea is emblematic of my entire dissertation. I set out to identify and fix the deficiencies that were preventing Cyclus from being useful for international safeguards, and it turned out that there were a lot of small things in the way instead of one large project. Research works this way sometimes.

Now that Cyclus simulations include the capabilities needed to produce data for nuclear material accounting reports, the next part of my work creates the capability to generate those reports for any hypothetical set of nuclear facilities over any length of time.

Turning Cyclus simulations into synthetic nuclear material accounting reports

One of the requirements for non-nuclear-weapon States is to submit information about the location, composition, and movement of all nuclear material in their country. The system for how to do this was developed decades ago around punch cards. While our computer systems have evolved significantly in the intervening years, the format for submitting nuclear material accounting reports remains linked to the style of punch cards. This system is typically called Code 10, because it is described in the tenth part of the model agreement that countries arrange with the IAEA.

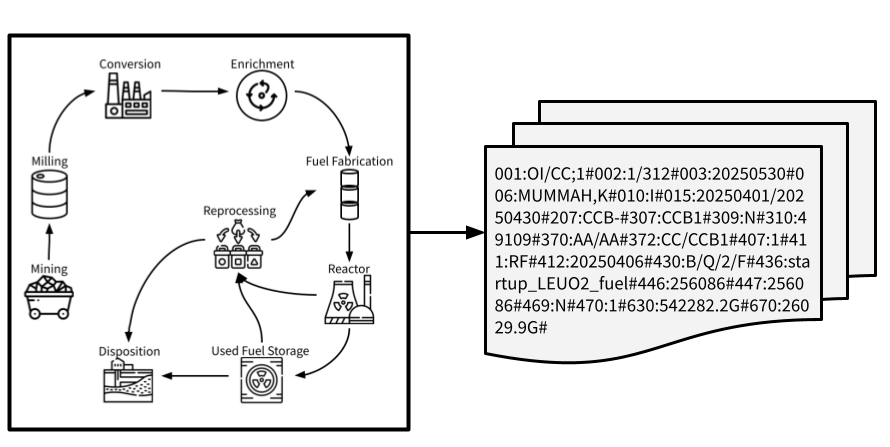

The end result of Code 10 report snippets looks a bit like a small child mashing a keyboard, but it contains everything the IAEA knows about nuclear material movements!

The end result of Code 10 report snippets looks a bit like a small child mashing a keyboard, but it contains everything the IAEA knows about nuclear material movements!

Real nuclear material accounting reports are in the Code 10 format, so replicating this information synthetically using computer simulations should be in the same format, too. Models trained on synthetic data could relatively easily be used on real data, and using this format ensures that only the information contained in real reports is incorporated into the synthetic reports.

Cyclus generates a lot of information that doesn’t end up in nuclear material accounting reports. For example, some of the internal movements in a facility are simulated in Cyclus but do not count as “inventory changes” under the purview of Code 10. If I trained a model to look for signs of nuclear material diversion using the entire Cyclus simulation, I would capture this excess data that the IAEA does not have for real countries, which is undesirable.

Converting a Cyclus simulation into Code 10 format reports is a bit like translating between two languages. Some of the information has a very straightforward translation, such as time. Others require new context, such as converting the individual processes of a nuclear fuel cycle into the regions of importance to safeguards, called material balance areas.

Finally, some ideas only exist in one “language” or another. Cyclus simulates nuclear materials as masses, but some entries in the Code 10 reports are based on volume. The conversion from mass to volume can be straightforward. If you remember back to high school science class, density is mass divided by volume. Rearranging this equation results in volume equals mass divided by density. However, density is not a concept that exists in Cyclus, so some special handling is required to overcome this limitation. This is one way where the new nuclear material packaging capability from the previous section comes in handy. Nuclear material packages have a specific mass and a specific volume (implying a specific density), and therefore, when nuclear materials are shipped between facilities using these packages, it is possible to know their volume.

With this new tool, it is now possible to simulate the movement of nuclear material from mining to disposal for an entire country over the course of decades and then see what nuclear material accounting reports should look like for that entire period. The final step of this work is to create realistic but fake countries to demonstrate all these new capabilities together.

Creating realistic but fictitious countries

Computer modeling frequently creates worlds that do not exist. Often, this is some possible near future, something that could happen to a real system if it evolved in a certain way. This is very common in nuclear fuel cycle modeling; if you want to see how a fleet of nuclear waste-burning reactors would work, it makes sense to start from a real country that already has nuclear reactors.

In some cases, though, it doesn’t make sense to start from a real country. Real countries are complicated, and the details may not be publicly available. Existing nuclear fuel cycles may not be a good proxy for “nuclear newcomer” countries that are building their nuclear power system from scratch in the 2020s and beyond rather than the 1960s and 1970s. And in the case of international safeguards, real countries are political. Using a real country for a demonstration, even with innocuous intentions, could accidentally make a political statement about which countries “should” be considered as possible proliferators.

Researchers often come up with one-off fictitious countries to use in their work. My team at LANL did this for a project report. A PhD is a chance to do research in a more robust way, however, so I decided to develop a methodology to comprehensively describe a nuclear fuel cycle and then generate a set of fictitious countries.

I built on a 2014 study for the U.S. Department of Energy, called the Nuclear Fuel Cycle Evaluation and Screening – Final Report (E&S) study, that aimed to describe nuclear fuel cycles using six specific parameters, but did not attempt to build entire fictitious countries. I found that I needed to expand to fifteen parameters to more comprehensively describe the nuclear reactor system, the type of fuel recycling used, and the other facilities in the fuel cycle.

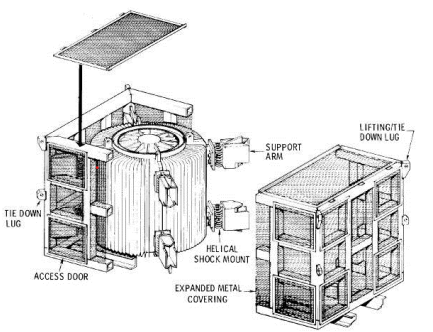

Then, I got to work using my parameters to build a set of thirteen fictitious countries, which I call cases. These are, obviously, not a comprehensive list of possible fuel cycles. The E&S study produced almost 4,400 reactor systems and was able to group them into 40 similar categories. With all the extra parameters I added, it would not be useful or feasible to enumerate all the possible permutations, even after getting rid of options that would not be possible due to physics.

Instead, I carefully constructed the fake countries such that all the options for each parameter were used in at least one fake country. Consider one of my parameters, reactor power. Reactors are categorized as micro, small, medium, or large, depending on the amount of power they produce. At least one fake country has a reactor at every power level. The smallest design, in Case 4, uses microreactors that produce only 2 megawatts of electricity, or about the same as a single modern wind turbine. The largest in Case 10 produces over 1300 megawatts, which at the typical capacity for a nuclear power plant would produce the same amount of annual electricity as is consumed in the state of New Hampshire5.

This is some of the information associated with each of my fictitious countries. The reactors are defined in enough detail that they can be modeled in similar computer codes, and the nuclear fuel cycle includes information on which facilities exist within the country (materials from the missing facilities have to be imported from another country).

This is some of the information associated with each of my fictitious countries. The reactors are defined in enough detail that they can be modeled in similar computer codes, and the nuclear fuel cycle includes information on which facilities exist within the country (materials from the missing facilities have to be imported from another country).

Conclusions

The final step of my research was to demonstrate the types of analyses that people could do with the new capabilities I developed. Eventually this work might be used to look for subtle patterns that could indicate nefarious actions, but first I needed to show how we could model and then analyze benign disruptions to the system. I showed how future users could run many iterations of simulations with slight changes and evaluate what, if any, effects are detectable elsewhere.

Until now, no one has claimed to be able to generate an entire country’s worth of synthetic nuclear material accounting reports. This represents a significant new capability that can open new doors in the fields of nuclear fuel cycle modeling and international safeguards.

In an ideal world, someone with all the information about a country’s nuclear fuel cycle (real or fictitious) would use my tools to generate millions of plausible nuclear material accounting reports. This information could be used to look for novel signatures of bad behavior, like nuclear material diversion, and to test how new nuclear facilities would fit into the safeguards structure. This work requires fuel cycle expertise and a significant amount of data science (including machine learning) expertise to parse the generated data. Although it was out of the scope of my Ph.D. work, I hope that it can eventually happen.

References

- “Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons,” (Jun. 1968).

- A. WELLERSTEIN, “Counting the dead at Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (Aug. 2020).

- P. A. KHARECHA and J. E. HANSEN, “Prevented Mortality and Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Historical and Projected Nuclear Power,” Environmental Science & Technology, 47, 9 (Mar. 2013).

- “Scientific and technical aspects of the control of atomic energy: The full text of the first report of the Scientific and Technical Committee of the Atomic Energy Commission, the background of the report, a glossary of scientific terms and biographical notes,” Tech. rep., United Nations Atomic Energy Commission, Scientific and Technical Committee (Sep. 1946).

- “Electric Power Annual 2023,” Tech. rep., U.S. Energy Information Administration, Washington D.C., United States (Oct. 2024).

Comments